MIOARA ZOUTEWELLE-TEROVAN & AART LIEFBROER

During the last half century, Europe has witnessed a significant increase in the older population. In most European countries life expectancy has increased from approximately 70 years in 1960 to 80 years in 2014. Proportions of the total population aged 65 and over have increased substantially from about nine percent in 1960 to 19 percent in 2015. In an ageing society, understanding the risk factors for well-being is essential. Among older individuals, loneliness – the dissonance between one’s desired and the actual quantity and quality of social contacts – represents a major threat to well-being. Studies have shown that older persons who lack an intimate partner have financial problems or experience poor health and run a higher risk of experiencing loneliness. However, we know little about the long-term consequences of family experiences occurring earlier in life, i.e. during young- and mid-adulthood.

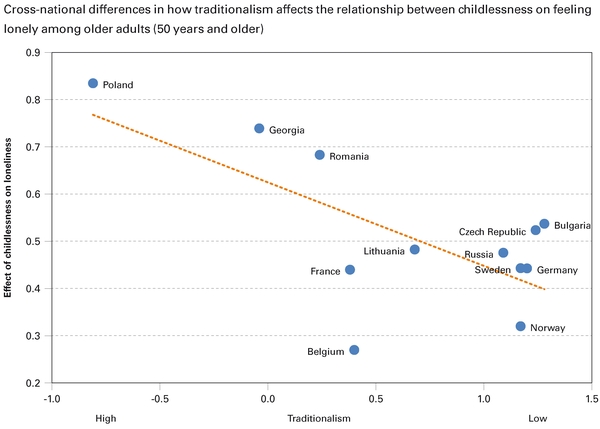

In this study we examine whether individuals who remain single and childless throughout their life suffer more of loneliness at older ages (50 years and older) than individuals who do make family transitions such as forming a union with a partner and/or having children. In the 12 European countries studied (Bulgaria, Belgium, Czech Republic, France, Germany, Lithuania, Norway, Poland, Romania, Russia, Sweden and Georgia), older individuals were lonelier if they had never lived with a partner during their life. However, the strength of the effects varies across nations but without revealing a clear geographical pattern. Individuals in Bulgaria who never lived with a partner are the loneliest at later ages, whereas the negative consequences of never living with a partner – with respect to loneliness – are less severe in Romania and France. Childlessness is also perceived as a deviation from the norm and childless individuals were lonelier in all countries investigated. Still, in Eastern Europe (Poland, Georgia, and Romania) the consequences for loneliness were stronger compared to Western and Northern Europe (Belgium, France, Norway and Sweden).

We further tried to explain these differences across countries and assumed that in countries where ‘traditional’ family norms and values are strong, such as in Southern and Eastern Europe, non-compliance with social norms will have stronger negative consequences for loneliness than in Western European countries. A noteworthy result is that in countries scoring high on traditional family values, the negative impact of childlessness on loneliness is almost double compared to countries scoring low on traditionalism (see the figure).

In our study we also argue that attention should not only be paid to whether family events occur, but also to the timing of these events: when they occur. Persons who enter intimate relationships or parenthood earlier or later compared to their peer group may feel pressured and marginalized and may on that account feel lonelier later in life compared to the ones experiencing these events ‘on time’. Our results show that whereas early partnering or parenthood seem to have a weak or no effect on loneliness in old age, postponement of family formation events plays a more important role in feeling lonely. Starting to live with the first partner later than the peer group is linked to higher levels of loneliness. This effect was particularly strong in Lithuania, Germany, France and Norway. Late parenthood was also linked to later life loneliness, and the most negative consequences were observed in Bulgaria, Romania, Poland, Belgium and Sweden. It may be that once young adults have passed the period during which these events are socially expected, the consequences in terms of their stigmatization may appear gradually under continuous peer and family pressure and penalties. Since loneliness is one of the strongest predictors of a low quality of life for the aged and has negative consequences in multiple life-domains – such as mental and physical health, economic hardship, and mortality – policies aimed at individuals with non-normative family transitions could reduce feelings of loneliness at older ages and improve well-being.

Mioara Zoutewelle-Terovan, NIDI, email: zoutewelle@nidi.nl

Aart Liefbroer, NIDI, email: liefbroer@nidi.nl

References

- De Jong Gierveld, J. & Van Tilburg, T. (2006).

- A 6-item scale for overall, emotional, and social loneliness confirmatory tests on survey data. Research on Aging 28(5), pp. 582-598.

- Inglehart, R. & Baker, W.E. (2000).

- Modernization, cultural change, and the persistence of traditional values. American Sociological Review , 65(1), pp. 19-51.

- Zoutewelle-Terovan, M. & Liefbroer, A.C. (2017).

- Swimming against the stream: Non-normative family transitions and loneliness in later life across 12 nations. The Gerontologist.