It is a regularly recurring theme among politicians worrying about low fertility rates: which set of social programmes and laws can help parents attain their desired family size? Men, but in particular women, face conflicts and trade-offs when it comes to combining making a living with taking care of their family. Research often shows that women in developed countries do not attain their desired number of children, in which case money, housing and working arrangements are named as barriers. At regular intervals one can also hear the calls from politicians to increase the fertility rate and to lower the barriers that young parents face. In the Netherlands, a conservative Christian party promised voters to increase family allowances and to give families an bonus of 1,000 euros with the arrival of a fourth child. In other countries as well, the baby bonus idea is seen as silver bullet solution – from Russia and Hungary to Australia, Italy and Spain. But how effective are these financial incentives and other family policy measures?

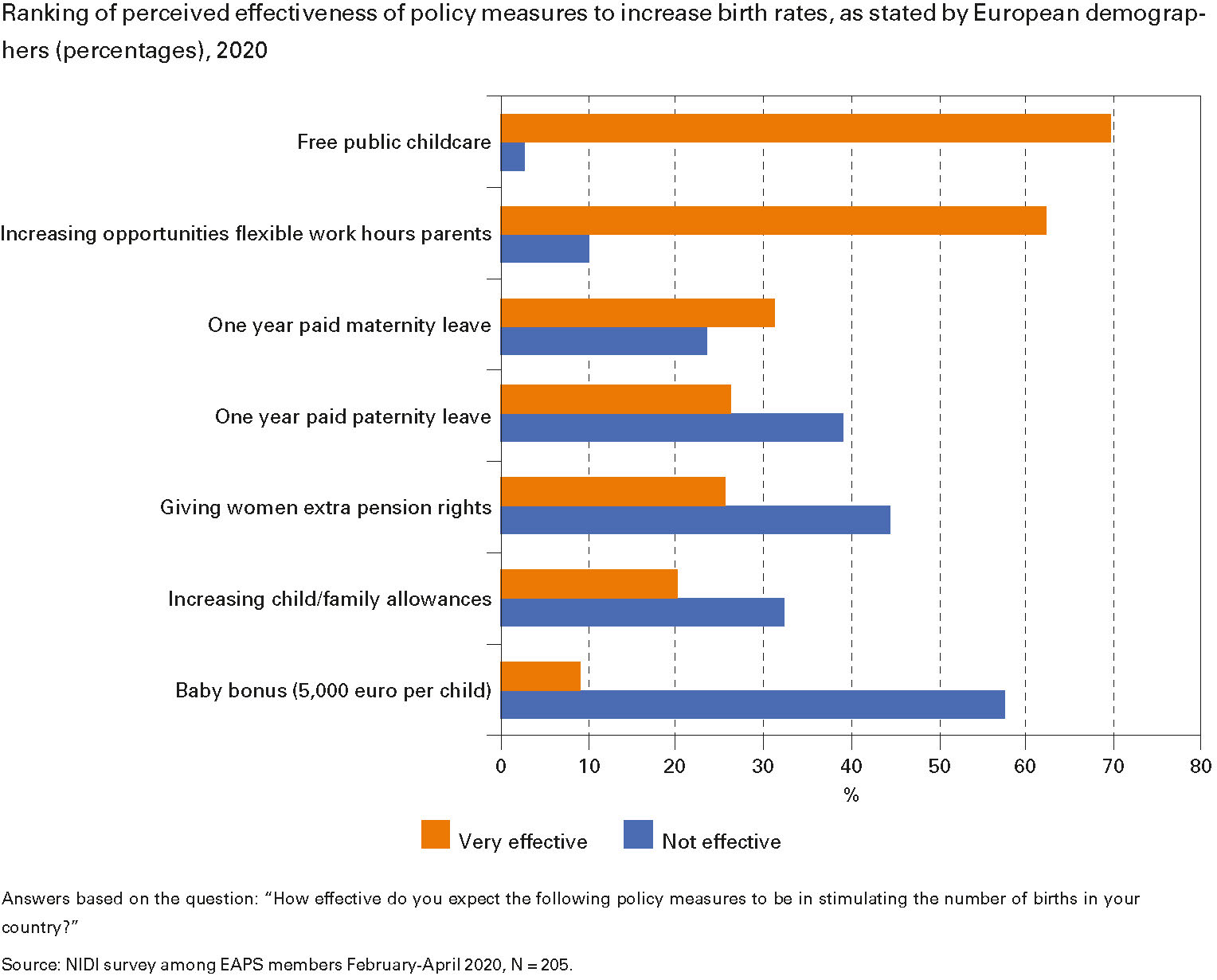

Two years ago, we asked members of the European Association for Population Studies (EAPS) how they viewed the effectiveness of family policy measures in the event that they were implemented in their country to increase the fertility rate. The figure below shows what demographers perceive as very effective – and in particular ineffective – measures.

‘Baby bonuses’ are by and large seen as highly ineffective. And to be frank, all measures that change the financial incentives of having a child or give allowances to soften the budget constraints of parents are met with skepticism. ‘Rewarding’ childbearing by giving women extra pension rights, something that was/is quite common in Eastern European countries, is seen as effective only by a small minority. Likewise, one-year paid maternal leave is not seen as a policy that will entice parents to have more children. However, two policy measures are seen as effective: free daycare and more flexible work arrangements to combine work and family responsibilities. The demand for flexible work arrangements is not surprising, as young parents are facing a tougher job market where full-time work is the norm to succeed and flexible contracts are the rule. Raising a child can then be an expensive or stressful responsibility. The observation that bonuses are not perceived to be effective is in line with research that shows no lasting effects of such measures. It could, of course, be the case that our proposed financial bonus (5,000 euros per child) is far too low to convince our respondents – but it may be far simpler: perhaps demographers think that you cannot put a price on having a child. Children are literally priceless, hence, every effort to change the minds of potential parents by using a ‘big carrot’ is going to be of no avail.

Harry van Dalen, NIDI-KNAW/University of Groningen and Tilburg University, e-mail: dalen@nidi.nl

Kène Henkens, NIDI-KNAW/University of Groningen and University of Amsterdam, e-mail: henkens@nidi.nl

Literature

- Van Dalen, H. P., and Henkens, K. (2021), Population and climate change: Consensus and dissensus among demographers. European Journal of Population, 37(3), pp. 551-567.