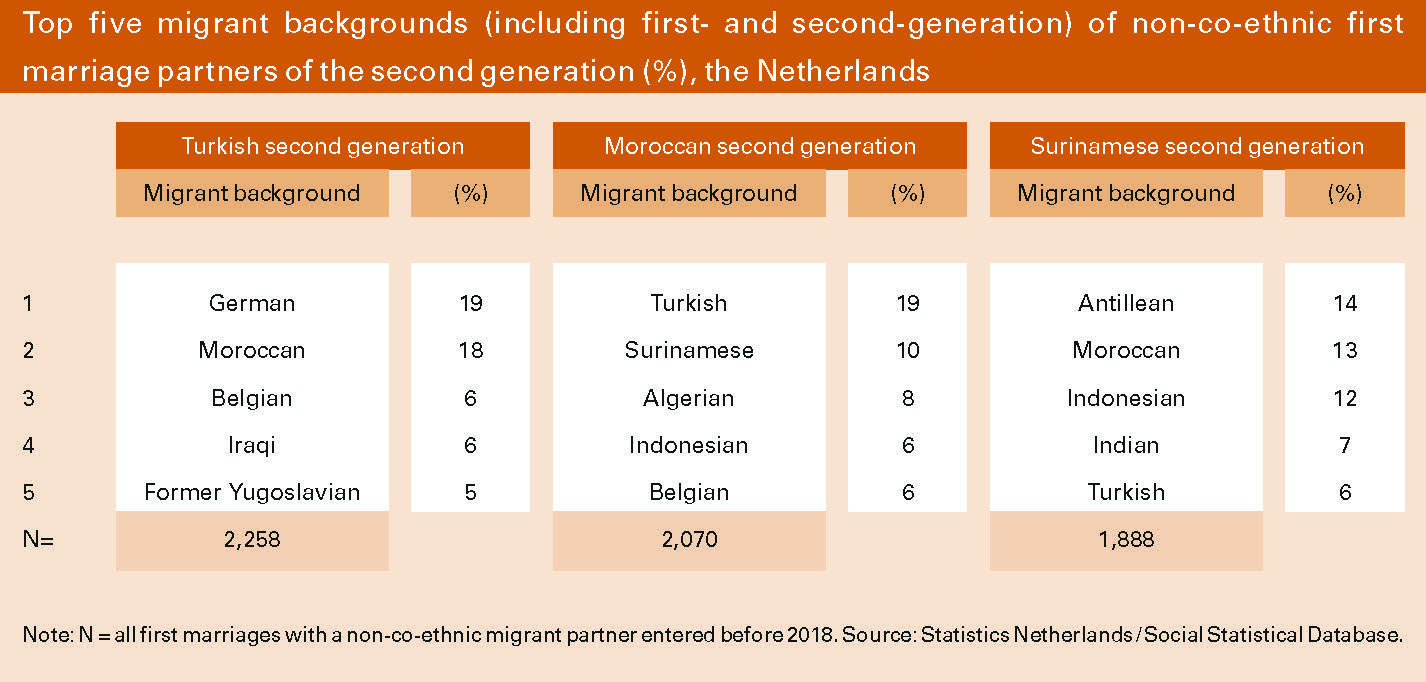

We listed the top five most common non-coethnic migration backgrounds of first marriage partners for the abovementioned origin groups born between 1980 and 1999 (see table). For the Turkish second generation, six percent of all first marriage partners had a non-co-ethnic migrant background. For the Moroccan and Surinamese second generation this was respectively 8 and 18 percent. As can be seen, there are clear differences in the migration background of these partners. For example, non-co-ethnic marriage partners of the Turkish second generation most often have a German background (19%), while partners of the Surinamese second generation are relatively often Antillean (14%).

Despite these differences, we can detect some general patterns. First, non-co-ethnic migrant partners are often part of the other four largest non-European migrant groups in the Netherlands, reflecting the importance of group size and meeting opportunities. Second, what appear to be interethnic partners may in fact be intra-ethnic partners, depending on the criteria used to determine what an intra-ethnic marriage is. Certain marriage partners share cultural and religious similarities as reflected in the countries of origin, such as Iraqi partners for the Turkish second generation and Indian partners for the Surinamese second generation. Third, partners relatively often come from neighbouring European countries. European immigrants make up a large share of the total migrant population and, moreover, it is relatively easy for partners to move to the Netherlands. However, the way migrant generations are defined in the Netherlands and many other European countries seems to disguise a particular type of intra-ethnic marriage: some first-generation European partners may in fact be part of the second-generation in their own country of birth.

Overall, these findings show that there is a range of origin groups hidden behind the overarching category of non-co-ethnic migrant partners. What does this mean for our thinking about interethnic marriages? Although the possible significance of interethnic marriages for integration and social cohesion is often mentioned, it proves difficult to define what an interethnic marriage actually is, especially for the second generation growing up in diverse societies, like the Netherlands. Is a marriage between partners of the Turkish and Surinamese second generation, for example, more interethnic than a marriage between a partner of the Turkish second generation born in the Netherlands and one of the Turkish second generation born in Belgium?

What becomes evident, however, is that partners with ‘non-co-ethnic’ migration backgrounds are not a homogeneous group, there is substantial diversity within this category. It is important to look beyond simple distinctions and dichotomies when it comes to partner choice, especially if we want to know more about the extent to which intra-ethnic relationships remain important for generations to come.

Gusta Wachter, NIDI-KNAW/University of Groningen, e-mail: wachter@nidi.nl

Helga de Valk, NIDI-KNAW/University of Groningen, e-mail: valk@nidi.nl