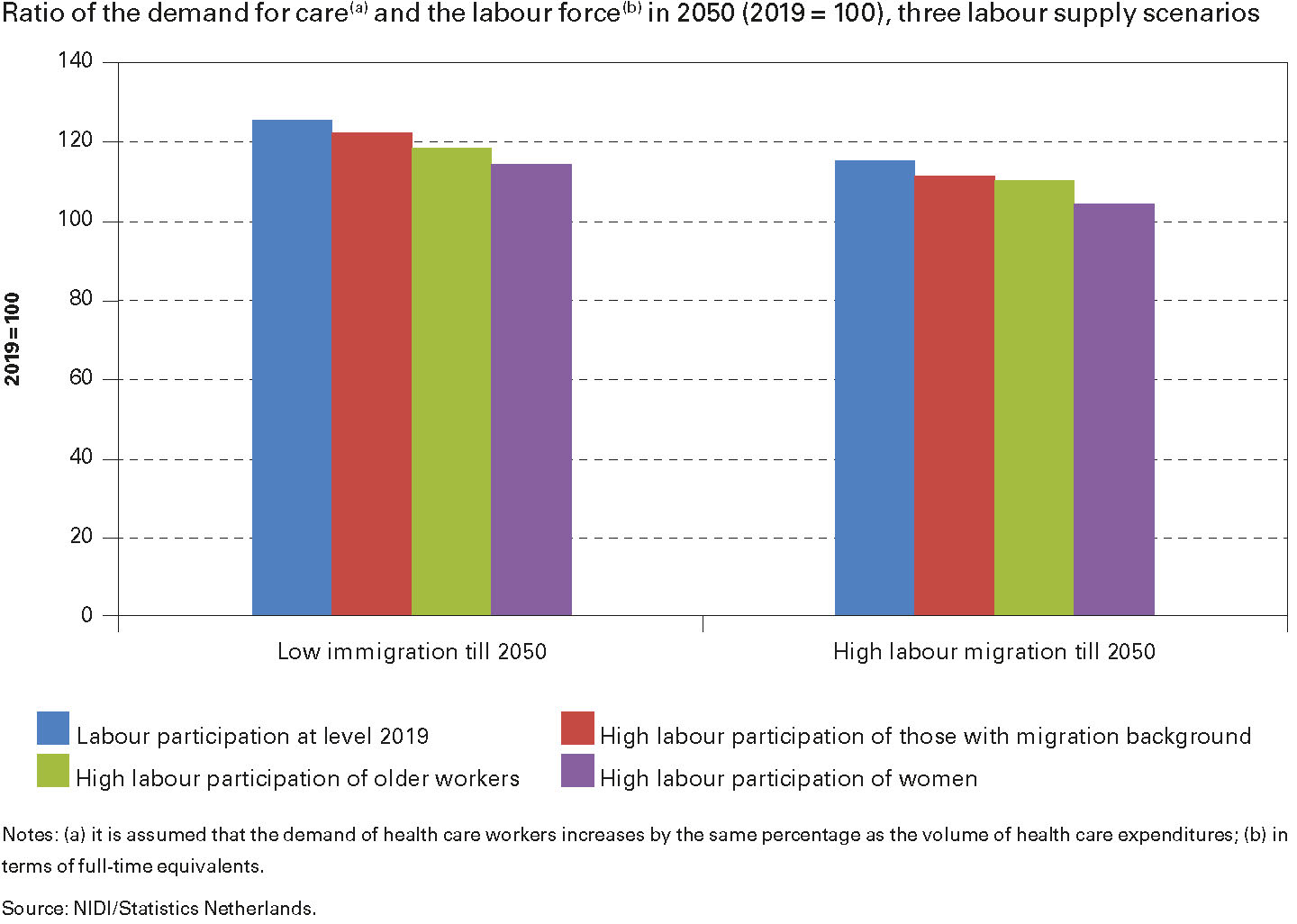

The demand for care increases sharply with age. The healthcare costs of people 80 years and older are considerably higher than the costs of 65 year olds. Among seniors (65+) there will be a sharp increase in the number of people over 80, which will in turn lead to a similar increase in the demand for care. Because the population will grow more strongly during periods of high migration than during low migration, we can expect a simultaneous sharp increase in the demand for care. A high net immigration of around 90 thousand persons per year on average until 2050 will lead to a population growth over this period of 19 per cent, while under the conditions of a low net immigration of around 20 thousand persons per year the population in 2050 will be only one per cent larger than it is now. With a high net migration, the combination of population growth and ageing leads to a 28 per cent increase in the demand for care, and under conditions of a low net immigration to an increase of 17 per cent.

With a high net immigration including a high share of labour migrants, the labour force will increase by 11 per cent over the next thirty years. With a low net immigration, the labour force shrinks by seven per cent. In this projection, we have assumed that the labour force participation rates distinguished by age, gender, migration background and education level will be the same in 2050 as in 2019; in which case, the growth of the working population will be lagging behind the growth of the demand for care. The figure above shows that with low immigration, the ratio between the level of demand for care and the size of the labour force will increase by 25 per cent in the next thirty years, whereas with high migration, by 15 per cent. A high level of immigration therefore reduces the tension between the demand for care and the working population, but does not prevent the growth of the working population from lagging behind the growth in the demand for care.

Higher labour force participation

The growth of the labour force depends not only on the level of migration, but also on changes in employment rates. We have calculated three ‘what-if’ scenarios that show the effects of higher employment rates for people with a migrant background, the elderly and women. For migrants, we assume that the difference in their labour participation compared to the population without a migration background will decrease by 50 per cent by 2050 and that the participation of the children of migrants will then be just as high as the population without a migration background. For the elderly, we assume that older workers will continue to work for the same number of years as the increase in the statutory retirement age (which is linked to the increase in life expectancy at age 65). For women, we assume that the percentage of women in paid work in 2050 will be the same as the current percentage for men and that the difference in the proportion of women working parttime compared to men will decrease with 50 per cent by 2050.

The figure shows that the higher labour participation of women in particular has a major effect. With low net immigration, high female labour participation leads to an increase in the ratio between the level of care demanded and the size of the labour force by 14 per cent instead of 25 per cent. This is almost the same as with a high net immigration balance without a change in the labour participation rate. In terms of the size of the labour force, the effect of a higher labour force participation by women is therefore comparable to the effect of higher net immigration.

Health improvements

The tension between the level of the demand for care and the size of the working age population can also be reduced by curbing the growth of the demand for care. The demand for care by people with lower levels of education is higher than that of people with a higher level of education. We have calculated a ‘what-if’ scenario, in which we assume that the health of the lower educated will improve to such an extent that the differences in the demand for care according to education levels will disappear by 2050. In this scenario, the demand for healthcare would be ten per cent lower in 2050 than if the health inequalities were not reduced. In terms of size, this is comparable to the effect of higher female labour participation.

Policy choices

Population ageing means that the tension between the demand for care and the size of the working population is increasing, but the tension can be reduced by a mix of higher labour immigration, higher labour force participation and a reduction in health inequalities. Migration is a hot topic in Dutch public debate. If policymakers want to admit fewer migrants, they must realize that labour force participation must increase in order to maintain the working population. To achieve this, investments are needed in education and the promotion of healthy lifestyles. This may also contribute to slowing down the growth in the demand for care.

Joop de Beer, NIDI-KNAW/University of Groningen, e-mail: beer@nidi.nl

Literature

- NIDI & CBS (2021), Bevolking 2050 in beeld: opleiding, arbeid, zorg en wonen. Eindrapport Verkenning Bevolking 2050, Den Haag: NIDI.