The State Commission published its report (407 pages) on January 15. The commission of 13 eminent members from policy, politics and science offered a response to the government’s questions as to how demographic developments will affect numerous domains in society, and what should be done about it. As in other countries, population ageing and immigration are the focus of attention in the public debates. In numerous countries, the rising levels of immigration have led to upheaval. Such voices of discontent have also become stronger in the Netherlands and finding a middle way in the making of policy has also become more difficult. To gather insight into the interaction between population dynamics and society, in 2021 the Dutch parliament requested that the government establish a special State Commission on demographic developments. Its main tasks were to give a perspective on the most probable demographic developments and offer policy options that are suited to deal with the prospect of an ageing, more diverse and (potentially) growing population. The commission examined in particular the economic implications of population ageing and migration and how these two forces affect the use of space, the economy at large, and various public domains, like social security, health care and education.

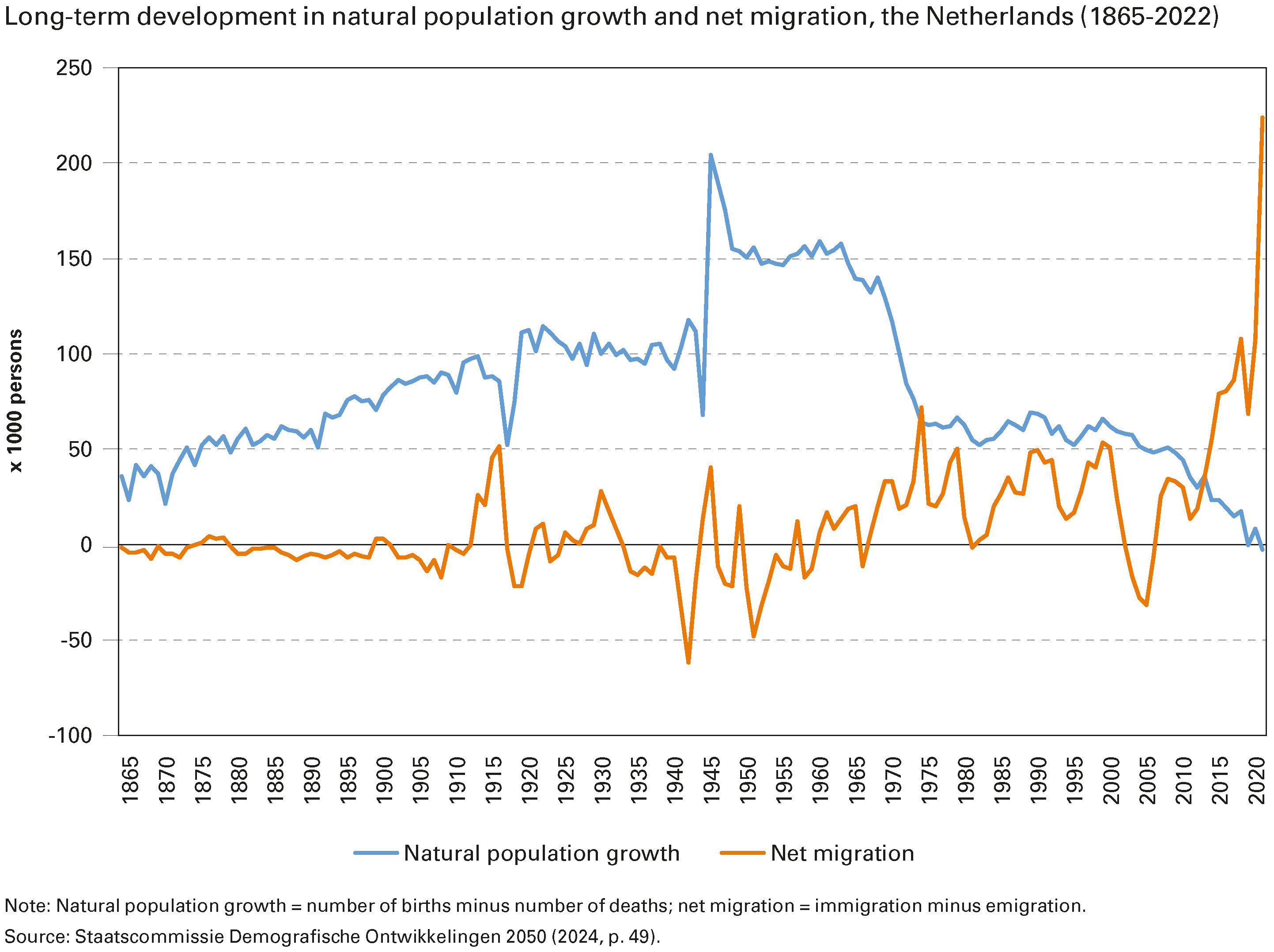

The Commission assessed that the growth of the Dutch population is primarily driven by migration (see figure below for a historical overview), and will most likely remain so in light of low fertility levels among the residing population. Without migration, the Dutch population would be in decline. Current immigration levels are driven by forces of globalisation and labour demand – triggering labour migration – and geopolitical tensions leading to recurrent peaks in refugee and asylum migration. It was also acknowledged that parts of these migration flows are more difficult to steer than others. Indirect policy measures that would, for instance, change the economic structure of the Netherlands and thereby the labour demand for migrants, may be just as important as direct migration measures that affect legal entry into the country. The Commission highlighted that the fact that economic forces and migration developments are tightly related should be recognised in policy design. In addition, not all migration policies fall under the mandate of the national government, such as free mobility within the EU or international agreements on asylum and refugees. Given this complexity, the Commission advised that it is crucial to capitalise on the available skills among those who arrive in the Netherlands, irrespective of their motive, including those who are simply granted asylum.

With respect to addressing the economic and social consequences of population ageing, the Commission recommends that economic policy should aim to facilitate innovation to increase (labour) productivity, decrease inequalities in life expectancy, increase healthy life expectancy and increase work force potential. Investing in education throughout the life course, working longer and/or increasing the number of hours worked should all be considered according to the Commission. Part-time work is the norm in the Netherlands (in particular among women), and the annual number of work hours per capita remains low. Public sectors like healthcare and education already face labour shortages, which make it difficult to offer quality services to every citizen; these shortages will probably remain in force in the coming decades if nothing is done.

The main reason for the Commission to plea for a moderate population growth rate is also a pragmatic one. Both rapid population growth as well as population decline were considered to be unsustainable. Moderate growth is considered the best course of action, also given the fact that population decline would result in even more drastic population ageing and related questions on sustainability of social services, including healthcare demands. The prospect of high levels of population growth were also evaluated to be undesirable in a country where the housing market is already overheated, offering for example little opportunity for young people to find suitable and affordable housing, and where shortages in public services are rife. The State Commission emphasises that in the long run, the Dutch government and society in general should reflect on and make choices about which type of society and economy it wants to strive for. This can imply that there should be less focus on sectors that can only exist by virtue of cheap labour and exploitation of migrants, and more focus on sectors that add real and lasting value and which make the most of the potential and skills belonging to a well-educated population.

Note: Helga de Valk is vice chair of the State Commission (SDO 2050), Harry van Dalen is scientific secretary of the State Commission.

Helga de Valk, NIDI-KNAW/University of Groningen, e-mail: valk@nidi.nl

Harry van Dalen, NIDI-KNAW/University of Groningen and Tilburg University, e-mail: dalen@nidi.nl

Literature

- Staatscommissie Demografische Ontwikkelingen 2050 (2024), Gematigde groei. Rapport van de Staatscommissie demografische ontwikkelingen 2050. The Hague.